https://watch.screencastify.com/v/IWVGFLNYJeZtb6UnNQbj

T. Thomas Fortune and Ida B. Wells: Militant Activism in the Age of Accommodation

The year was 1909, Ida B. Wells, famed anti-lynching advocate, journalist, and suffragist was called upon by Dr. W.E.B. DuBois to attend the National Negro Committee, a three-day meeting that founded the NAACP. She encouraged T. Thomas Fortune, owner of The New York Age and founder of the Afro-American League, and other early civil rights friends to attend by informing them Booker T. Washington, leader of the movement, would not be involved and she was nominated to be an active member of the committee. A growing rift between Washington’s theories of industrial education and DuBois’ racial uplift necessitated the establishment of a new organization. However, when DuBois announced the members, she was not included. He later confessed he purposefully left her name off the list and replaced her with a man’s, Dr. Charles E. Bentley, a dentist. He explained he felt Wells would be represented by another woman activist in Chicago leaving Dr. Bentley to represent the Niagara Movement. Wells felt deeply slighted, “it was evident someone did not want my presence,” but many of the white members like co-founder Mary Ovington had her name re-instated. The selecting committee quickly aimed to rectify the situation and expressed their shock that DuBois omitted her name[1].

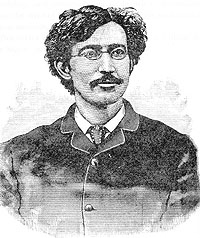

Compared to DuBois, Fortune was very egalitarian when it came to women joining the male-dominated spaces of leadership and activism. After all it was Fortune that notified Wells about the attack on her Memphis newspaper and then offered her a job writing for his paper. He even opened his home to her until she could find a place for herself. Most people are familiar with the great activist of the times: Frederick Douglas, Booker T. Washington, Ida B. Wells, and W.E.B. DuBois however few know T. Thomas Fortune. He had a tremendous influence on Ida B. Wells and the early civil rights movement. Their friendship lasted many decades, but they drifted apart. Who was T. Thomas Fortune on a deeper level? What was the extent of the relationship between Fortune and Wells? What caused them to drift apart?

T. Thomas Fortune confidently called himself an agitator while others called him a militant of the early civil rights movement. As one of the most prolific black newspaper publishers of the Progressive Era he was a man ahead of the times. He called for reparations for formerly enslaved people, desegregation, equality among the races, and inclusivity of women in politics. He created the Afro-American League which served as a model for the NAACP. He had the courage to speak out against racial injustices toward African Americans but has been largely overlooked by historians. He believed in agitation and creating disorder in the South during a time of accommodation. It was their solution to white mobs, lynching, and the murder, and rape of Afro-Americans. He used his platform and newspaper The New York Age to demand civil rights for African Americans. He worked alongside many notable African American leaders: Frederick Douglas, Ida B. Wells, Booker T. Washington, W.E.B. DuBois, and Marvin Garvey. President Theodore Roosevelt appointed him special envoy to the Philippines where he wrote a report warning the United States about Japan[2].

Although many historians have overlooked T. Thomas Fortune, he had a powerful influence on Ida B. Wells’ anti-lynching movement. Through their writings one can feel their pain as well as sense of optimism. By examining T. Thomas Fortune’s life along Ida B. Wells’, you can see how they used their words as tools to fight against systems of oppression. And they were not alone, they were part of a community of activist that debated how to defeat white supremacy and strategized about how to achieve equal rights and economic independence for African Americans.

The black press had considerable influence over the black community. Bruce J. Evensen stresses their importance: “Just as abolitionism was the cause that animated and united the black press in the mid-nineteenth century, the anti-lynching [crusade] united black newspapers later on in the century,”[3]. Fortune moved to New York City in 1879 and within four years became the editor of a black-owned paper, The New York Globe (known later as the New York Freeman and then The New York Age). He led the paper for fourteen years and eventually became an owner[4].

During Reconstruction many African Americans like Fortune and Wells benefitted by receiving an education while living in the former Confederate states. However, Reconstruction policies were dismantled after 1876 with the controversial election of President Rutherford B. Hayes. Southern states passed new state constitutions that permitted white supremacist racial politics to overturn civic, social, and political rights of African Americans. Blacks living north of the Mason-Dixon line also began to lose political rights. Historian Shawn Leigh Alexander explains their responses: “African American leaders and activists responded in many ways ranging widely from self-help and racial solidarity to economic nationalism, emigration, and political agitation,” [5]. Fortune fled Florida and moved north to marry a former enslaved woman he knew named Carrie Smiley[6] while Wells lived with her family in Tennessee[7].

There was a spectrum of responses to Jim Crow from radical to moderate. African American men and women actively fought oppression by forming national civil rights organizations. In the Jim Crow Era, African Americans’ perceived inactions was called the accommodation, however that deceives one into thinking they accepted the status quo. Oppressed people may challenge their oppressors in various forms of protest, for example, in songs, theft, or vandalism. Very rarely will marginalized people visibly or explicitly challenge their oppressors or their institutions. Even Booker T. Washington, the accommodationist, secretly challenged Jim Crow. These daily acts of insubordination are what historian Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham coined “micropolitics,” the use of formal and informal power by individuals or groups to achieve their goals within society[8]. It is important to recognize the voice of the voiceless.

There is little scholarship on the influence Fortune had on Wells. Historians who have written about Wells have maintained she was a religious, gender activist, but scholar Tommy J. Curry states she was more heavily influenced by Afro-American male militant, agitators like Fortune, Jim Wells, and Frederick Douglass[9]. Historian Claudia D. Nelson attests, “men in her life encouraged her to step outside the purview of what society believed a woman should do and be. She had a solid support system from the moment she entered the world to the peak of her anti-lynching campaign and civil rights, human rights, and women rights activism,”[10]. Historians have focused on how activist men influenced Wells, but little is known about the life long friendship between Wells and Fortune.

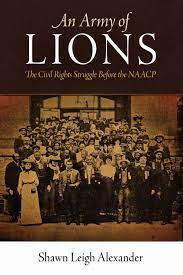

Historians often diminished or ignored Fortune’s social activism. When it comes to African American leaders and early civil rights organizations, “Du Bois has mistakenly become central to our understanding of this period of African American history. His leadership role in the Niagara Movement, for example, has obscured how others have perceived and studied the era. As a result, scholars have often agreed with Du Bois’s and historian Herbert Aptheker’s assertion that only the Niagara Movement influenced the founding of the NAACP,”[11]. Alexander’s groundbreaking book, An Army of Lions: The Civil Rights Struggle Before the NAACP, sheds light on the early civil rights leaders as they grappled with ways to uplift the black community and agitate white supremacy in the United States. Fortune’s Afro-American Council created a legal bureau which allowed them to aggressively pursue litigation cases across the nation such as new voting restrictions passed by southern states. Alexander depicts Fortune as a charismatic leader, the next generation of abolitionists, and an advocate for Black self-defense[12].

Fortune was the founder, editor, and builder of The New York Age, the most subscribed black newspaper of its time. The Chicago Defender called it “the first newspaperman’s newspaper,”[13]. His story is remarkable since he was a born an enslaved person five years before the Civil War and later received an education through the Reconstruction period. Before he served as a famed editor, he was a page in the Florida state senate, worked in a post office as a mail clerk, and served as an Inspector of Customs[14]. He was the ghost writer behind Booker T. Washington’s autobiography, gave Washington the nickname “The Wizard,” and he also served as Washington’s adviser. He mentored a young W.E.B. DuBois, who wrote for his paper[15].

Ida B. Wells was also born into enslavement. She lost her parents at an early age, and began working to support her siblings. She started her own paper, Free Speech and Headlight in Memphis, Tennessee. Wells began her anti-lynching campaign following the lynching of a friend by a white mob in 1889. A couple of years later a mob attacked and burned down her offices after she wrote Southern Horrors: Lynch Laws in All its Phases[16]. Fortune came to her assistance and offered her a job with The New York Age.

Fortune became an early supporter of Wells, who was beginning her journalism career, by writing several editorials in the Freeman about Wells’ railroad discrimination case. This demonstrates his egalitarian beliefs towards the inclusion of black women voices in the struggle. Pursuing Civil Rights lawsuits became a staple in all his future political organizations[17]. After meeting her in person for the first time at a press convention in Washington D.C in 1889 Fortune wrote of her, “She has become famous as one of the few of our women who handle a goose quill with diamond point as easily as any man in newspaper work. If Iola [Wells’ pseudonym] were a man, she would be a humming independent in politics. She has plenty of nerve and is as sharp as a steel trap”[18]. Although this was meant as a complement such commentary points out that speaking for the race was a man’s job.

Fortune was the person who brought Ida B. Wells to New York City in 1892 following the attack on her Memphis newspaper and gave her the opportunity to continue writing about lynching in the South[19]. In her autobiography she states, “Had it not been for the courage and vision of these two men [T. Thomas Fortune and Jerome B. Peterson owners and editors of The New York Age], I could never have made such headway in emblazoning the story to the world. These men gave me a one- fourth interest in the paper in return for my subscription lists, which were afterward furnished me, and I became a weekly contributor on salary.”[20]. Fortune was remarkably progressive and open to giving space to a woman in a male dominated field. Wells began to feel valued and empowered by Fortune and Peterson. According to Wells,

“The Negro race should be ever grateful to T. Thomas Fortune and Jerome B. Peterson that they helped me give to the world the first inside story of the negro lynching. These men printed ten thousand copies of that copy of the issue of the Age and broadcast them throughout the country and the South. One thousand copies were sold in the streets of Memphis alone. Frederick Douglas came from his home in Washington to tell me what a revelation of conditions this article had been to him,”[21].

Although the early civil rights era was known as the “age of accommodation” Wells and Fortune practiced active agitation. Both Fortune and Wells preached about using violence, self-protection, and armed resistance[22]. Due to death threats Wells began carrying a pistol, “a Winchester rifle should have a place of honor in every black home, and it should be used for that protection which the law refuses to give,”[23]. She felt if she could take out at least one white supremacist while they attacked her, she would accept defeat. Fortune also believed in fighting back against white aggressors. In an essay he wrote in 1886 Fortune declares, “there are times when oppressed people have no other medium through which to make their protest hear than that of violence,”[24]. Both felt the use of violence and retaliation against white lynchers and white communities that allowed lynching to happen was acceptable.

They used the tactic of agitation for change and developed social activism to defeat racial injustices. Both held the belief that, “whites are driven by economic interests rather than moral compassion with regard to the race problem and the white society utilizes the crime of rape and the punishment of lynching to cement the destruction of blacks in the South,”[25]. Fortune even spoke out against his own political party and encouraged his readers to do the same. Journalist Roscoe Conkling Simmons described Fortune’s outspoken confidence was unlike anyone else, “throughout his life when he was not denouncing Democrats for oppression of his people in the South, he was firing away at Republicans for desertion of their cause,”[26]. Fortune showed no fear speaking out against the racial injustices, “I must speak my thoughts; attack all parties; uphold any party; be for man and, when necessary, stand against any set of men,”[27]. His outspokenness made him a leader to many African Americans and other press outlets took notice of him.

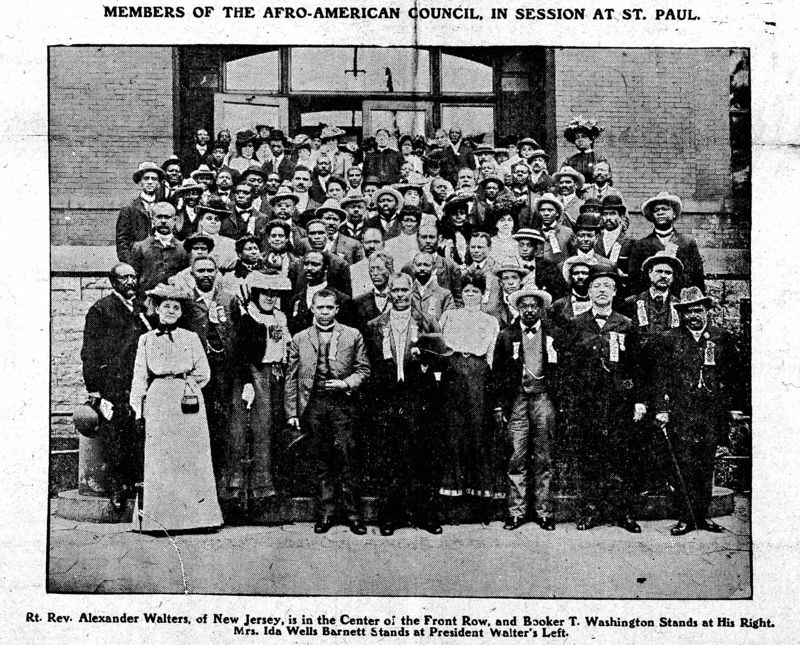

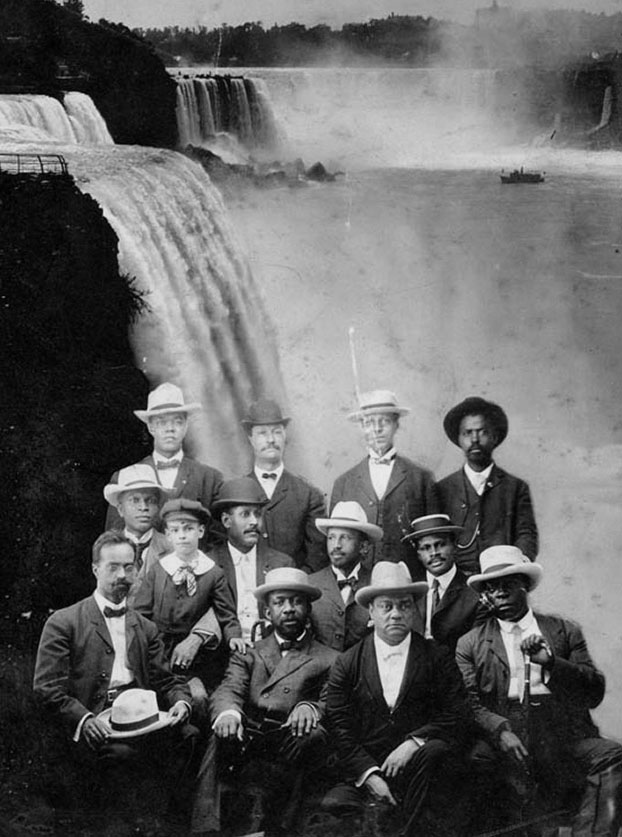

The Afro-American League formed in 1890 and the National Afro- American Council founded in 1898, were early political organizations that inspired the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People founded in 1909. These preceded DuBois’s 1905 Niagara Movement. These early civil rights organizations laid the groundwork for the NAACP’s civil rights activism. They developed critical strategies such as legal challenges to de facto and de jure segregation. The AAL and Council’s goals were to call attention to lynching and for the passing of protective federal laws. This marked the beginning of the anti-lynching movement[28].

After the death of Frederick Douglass, Fortune felt it upon himself to be the next leader of the movement. “Fortune’s Afro-American League, an organization that not only predated the NAACP, but was built on the agitationist philosophy of Fortune and rejected the idea that white involvement in Black struggles for social and political rights was useful or desirable”[29]. Fortune wholeheartedly believed in Afro-American leadership as necessary to success in any venture or any cause.

Twenty years after the death of Fortune The Chicago Defender journalist Roscoe Conking Simmons stated, “When the elite and the bookish gentry of pretensions arose against Washington and sought to slay him, it was Fortune who met the artillery of fierce denunciation with a pen that has had no equal in advocacy or controversy and routed the envious assault,”[30]. Washington used Fortune as his mouthpiece when a perceived wrongdoing occurred. Fortune could easily publish a pamphlet or article to denounce an issue Washington felt needed attention.

While Fortune used his editorship to speak out against racial injustices Wells went on two speaking tours of England and spoke at the behest of an aging Frederick Douglass. He felt she was the best person to tell them the deplorable conditions and treatment of Black Southerners[31]. She felt they sympathized more with Afro-Americans dating back to the American Civil War. Also due to economics of the cotton trade. Their agitator reasoning caused them to believe the English would sanction and condemn the United States and put an end to the racial violence[32]. Both aimed to appeal to an international audience to put pressure on the United States government to outlaw lynching.

Fortune and Wells became increasingly frustrated with the slow progress and their inability to reach mass popular support for the civil rights movement. After traveling across England for two years Wells returned to America and committed herself to another year of speaking tours, “After delivering my lectures I would remain in town long enough to make a personal appeal to the newspapers, to ministers of leading congregations, and wherever an opportunity was presented. For after all, it was the white people of the country who had to mold the public sentiment necessary to put a stop to lynching[33]. They both felt it was the duty of white Americans to stop lynching blacks and live up to the American ideals of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

After the death of Frederick Douglas black leaders of the movement fought each other to be the next face for racial equality. Fortune believed himself to be the next great leader but failed due to his personal struggles, professional conflicts, and political compromises. Even though he was a newspaper publisher and editor who helped create an Afro-American identity and helped expose the hypocrisy of racism, he never achieved the same level of leadership as Washington, DuBois, Wells, or Garvey. He was not the politician like Washington and did not have the grassroots support like Garvey[34]. Fortune desperately wanted to be the face of the movement, however by the late 1890s his prominence was plateauing while the others gained more popular support.

Scholars of Wells and Fortune have various interpretations on their professional relationship; however, their relationship clearly became strained as Fortune became more involved with Booker T. Washington. Wells, on the other hand, became associated more with women activists. She wanted to boost the number of women involved in the movement. She moved away from her male dominated circle of friends to engage and develop women activist. In 1895 she co-founded the National Association of Colored Women (N.A.C.W.)[35].

A widening rift between moderate Washington and the more radical DuBois and Wells placed Fortune in a dilemma. Privately Washington was more radical that previously acknowledged in that he believed in militant strategies and the use of court system, but publicly he followed accommodation because of the financial support from Northern white philanthropists and moderate white Southerners. According to historian Shawn Leigh Alexander, “the main reason the Afro-American Council did not become the civil rights organization was due to the many members who knew of Washington’s full “radical” involvement in the Council not being allowed by Washington to discuss this activity publicly. As a result, Washington’s demand for discretion regarding his public and private roles as well as his feuds with other civil rights leaders prevented the Council’s leaders from bringing individuals such as [William Monroe] Trotter and other Niagaraites into the fold,”[36].

In 1898 Fortune put out a call to resurrect the Afro-American League. Wells, having weaned her second child, decided to go to the convention in Rochester, New York despite being discouraged by Susan B. Anthony. Anthony believed Wells could not succeed being a working mother, however Wells felt she had a supportive extended family that enabled her to show others how it could be done. When she arrived, Wells was shocked by how Fortune spent most of his time berating Afro-American attendants for various perceived failures instead uniting them. His hot-tempered behavior also alarmed white audience members. When he named himself permanent chairman, Wells put a halt to the meeting and asked if he meant what he said earlier about the disparaging remarks about their own people. He doubled down and when the vote came up the crowd selected another member, Bishop Alexander Walters of the A.M.E. Church and Wells became the secretary of what became known as the Afro-American Council[37].

In 1899 Fortune wrote a letter to Washington describing Wells as a “bull in a China shop,” after the incident. Wells had recently spoken out against Washington in a scathing speech. Fortune was assuring the story would not be printed in his newspaper. Historian Jennifer Moses interprets his actions as jealousy, mutual sensitivities, and hotheadedness. Fortune was also going through several personal problems from the death of his father, brother, and a divorce. This led him to drink more, experience a mental breakdown, and other health issues. This incident also followed a previous disagreement between the two over the recreation of the Afro-American League. Wells was adamant about reorganizing while Fortune was very pessimistic and felt it would not be successful[38]. Their friendship was not the same after this moment.

In Wells’ autobiography she related a story about a lynching that occurred in Alabama in 1901 that demonstrates their disagreements. Washington refused to publicly condemn the violent act even though his organization, the Business League, wanted to. Fortune and other members “violently disagreed” with him and when they shared the news with Wells they were “very indignant” but there was nothing they could do because Washington had absolute control over the League. In the morning The Chicago Tribune gave Washington’s reasoning for not speaking out as “consideration for his school,” Tuskegee University[39].

Ultimately there are three reasons for the failure of Fortune’s organizations: finances, lack of media attention and ability to emanate information about the cause, and egos within the group. Fortune’s pre-NAACP organizations annual membership fee cost more than double of others[40]. The lack of funds meant they could not regularly communicate to their members by publishing information or open offices. Lastly, the Afro-American League and later Council had many egos contending to be the chief. What historian Alexander describes as “this inability to reach a practical accord, the debating frequently highlighted hairline cracks that often grew to cavernous proportions…This repeatedly led to splintering and the development of similar, yet rival organizations that competed for the same funds and attention from members of the race,”[41]. However, many of these strong personalities went on to successfully create the NAACP.

Fortune’s leadership began to wane as he sided with Washington taking over as the voice of the movement. By 1904 Fortune’s newspaper The New York Age was in financial trouble and Washington urged him to sell it to a private party. Little did Fortune know he was selling it to none other than Washington himself. He continued to write but became increasingly exhausted as he overextended himself. In 1906 with his divorce was finalized, he tumbled into a depression and further abuse alcohol[42]. His relationship with other black leaders had changed tremendously since his first publications in the 1880s.

While at the same time Wells’ fame continued to rise. She founded the N.A.C.W. along with Mary Church Terrell, Harriet Tubman, and Frances Harper. She walked in the Women’s parade. By 1897 they had fifty thousand members. Historian William F. Pinar describes the success of the organization had it, “linked and focused black women’s clubs and reform groups throughout the country; it’s meetings and publications provided forums where racial injustice, including lynching, could be discussed (Brundage 1993),”[43]. The N.A.C.W. was made up of mostly middle-class black women trying to define black womanhood is a positive manner. Public agitation, use of strong language in speeches and confrontation was seen as unwomanly. By ignoring these societal norms, Wells demonstrates her courage and determination to not be stopped even by black female critics[44].

By examining the lives of Fortune and Wells we began to see how black leadership and strategies of the early civil rights movement are more complex than previously stated by historians. Their personal stories illustrate how history shapes lives and beliefs, and those experiences impact and change history. Journalist Roscoe Conkling Simmons wrote about Fortune twenty years after his death calling him, “one of the great intellects of the centuries, the great man and soul who gave voice to a cause, shaped patriotism for the freed people, and prepared the way for the immortals works of his friend, Booker T. Washington,”[45]. Fortune’s downfall was publicly siding with Washington instead of Wells. Their progressive, egalitarian bond lasted decades and could have done more had they remained a united force. In an “age of accommodation” they knew the way towards racial equality and inclusion was to organize and agitate American society.

[1] Ida B. Wells-Barnett and Alfreda Duster, Crusade for Justice: The Autobiography of Ida B. Wells (Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press, 2020), https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.ezproxy.uhd.edu/lib/uhdowntown/detail.action?docID=6157250 , 276-279.

[2] Nina Tobier and E. L. Doctorow, “Elizabeth Bowser,” in Voices of Sag Harbor: A Village Remembered (Sag Harbor, New York: Friends of the John Jermain Memorial Library, 2007), pp. 39-44, 39-40.

[3] Nancy C. Unger, Christopher M. Nichols, and Wiley InterScience (Online service), “Lynching and the Black Press,” A companion to the Gilded age and progressive era – European University Institute, 2017, https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.ezproxy.uhd.edu/lib/uhdowntown/reader.action?docID=4788068&ppg=197 , 185.

[4] Jennifer Moses, “Writing ‘The Age: T. Thomas Fortune, the African American Press, and the Unfolding of Jim Crow America, 1880–1930. ”(dissertation, ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 2012), http://ezproxy.uhd.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/writing-age-t-thomas-fortune-african-american/docview/1112071746/se-2?accountid=7109, 1-2.

[5] Shawn Leigh Alexander, An Army of Lions: The Civil Rights Struggle Before the NAACP (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013), https://uh.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/discovery/openurl?institution=01UHO_INST&vid=01UHO_INST:DTOWN&rft.mms_id=991034167469405701&u.ignore_date_coverage=true, xi.

[6] Nina Tobier and E. L. Doctorow, “Elizabeth Bowser,” in Voices of Sag Harbor: A Village Remembered (Sag Harbor, New York: Friends of the John Jermain Memorial Library, 2007), pp. 39-44, 39.

[7] Ida B. Wells-Barnett and Alfreda Duster, Crusade for Justice: The Autobiography of Ida B. Wells (Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press, 2020), https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.ezproxy.uhd.edu/lib/uhdowntown/detail.action?docID=6157250 , 14.

[8] William F. Pinar, “PART THREE: Women and Racial Politics: CHAPTER 7: BLACK PROTEST and the EMERGENCE of IDA B. WELLS,” in The Gender of Racial Politics and Violence in America: Lynching, Prison Rape, & the Crisis of Masculinity (New York, NY: P. Lang, 2001), pp. 417-486, 422.

[9] Tommy Curry, “The Fortune of Wells: Ida B. Wells-Barnett’s Use of T. Thomas Fortune’s Philosophy of Social Agitation as a Prolegomenon to Militant Civil Rights Activism,” Transactions of the Charles S. Peirce Society 48, no. 4 (2012): pp. 456-482, https://doi.org/10.2979/trancharpeirsoc.48.4.456, 457.

[10] Tommy Curry, “The Fortune of Wells: Ida B. Wells-Barnett’s Use of T. Thomas Fortune’s Philosophy of Social Agitation as a Prolegomenon to Militant Civil Rights Activism,” Transactions of the Charles S. Peirce Society 48, no. 4 (2012): pp. 456-482, https://doi.org/10.2979/trancharpeirsoc.48.4.456, 458.

[11] Shawn Leigh Alexander, An Army of Lions: The Civil Rights Struggle Before the NAACP (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013), https://uh.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/discovery/openurl?institution=01UHO_INST&vid=01UHO_INST:DTOWN&rft.mms_id=991034167469405701&u.ignore_date_coverage=true, xiii.

[12] Shawn Leigh Alexander, An Army of Lions: The Civil Rights Struggle Before the NAACP (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013), https://uh.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/discovery/openurl?institution=01UHO_INST&vid=01UHO_INST:DTOWN&rft.mms_id=991034167469405701&u.ignore_date_coverage=true, 28-29.

[13] Roscoe Conkling Simmons, “‘THE SAGA OF T. THOMAS FORTUNE.” ,” The Chicago Defender, May 7, 1949, National Edition edition, p. 18, http://ezproxy.uhd.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/saga-t-thomas-fortune/docview/492779280/se-2?accountid=7109, 18.

[14] Roscoe Conkling Simmons, “‘THE SAGA OF T. THOMAS FORTUNE.” ,” The Chicago Defender, May 7, 1949, National Edition edition, p. 18, http://ezproxy.uhd.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/saga-t-thomas-fortune/docview/492779280/se-2?accountid=7109, 18.

[15] Tommy Curry, “The Fortune of Wells: Ida B. Wells-Barnett’s Use of T. Thomas Fortune’s Philosophy of Social Agitation as a Prolegomenon to Militant Civil Rights Activism,” Transactions of the Charles S. Peirce Society 48, no. 4 (2012): pp. 456-482, https://doi.org/10.2979/trancharpeirsoc.48.4.456, 457.

[16] Nancy C. Unger, Christopher M. Nichols, and Wiley InterScience (Online service), “Lynching and the Black Press,” A companion to the Gilded age and progressive era – European University Institute, 2017, https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.ezproxy.uhd.edu/lib/uhdowntown/reader.action?docID=4788068&ppg=197 , 185.

[17] Jennifer Moses, “Writing ‘The Age: T. Thomas Fortune, the African American Press, and the Unfolding of Jim Crow America, 1880–1930. ”(dissertation, ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 2012), http://ezproxy.uhd.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/writing-age-t-thomas-fortune-african-american/docview/1112071746/se-2?accountid=7109, 71.

[18] Ida B. Wells-Barnett and Alfreda Duster, Crusade for Justice: The Autobiography of Ida B. Wells (Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press, 2020), https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.ezproxy.uhd.edu/lib/uhdowntown/detail.action?docID=6157250 , 30.

[19] Tommy Curry, “The Fortune of Wells: Ida B. Wells-Barnett’s Use of T. Thomas Fortune’s Philosophy of Social Agitation as a Prolegomenon to Militant Civil Rights Activism,” Transactions of the Charles S. Peirce Society 48, no. 4 (2012): pp. 456-482, https://doi.org/10.2979/trancharpeirsoc.48.4.456, 457.

[20] Ida B. Wells-Barnett and Alfreda Duster, Crusade for Justice: The Autobiography of Ida B. Wells (Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press, 2020), https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.ezproxy.uhd.edu/lib/uhdowntown/detail.action?docID=6157250 , 54.

[21] Ida B. Wells-Barnett and Alfreda Duster, Crusade for Justice: The Autobiography of Ida B. Wells (Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press, 2020), https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.ezproxy.uhd.edu/lib/uhdowntown/detail.action?docID=6157250 , 62.

[22] Tommy Curry, “The Fortune of Wells: Ida B. Wells-Barnett’s Use of T. Thomas Fortune’s Philosophy of Social Agitation as a Prolegomenon to Militant Civil Rights Activism,” Transactions of the Charles S. Peirce Society 48, no. 4 (2012): pp. 456-482, https://doi.org/10.2979/trancharpeirsoc.48.4.456, 465.

[23] Nancy C. Unger, Christopher M. Nichols, and Wiley InterScience (Online service), “Lynching and the Black Press,” A companion to the Gilded age and progressive era – European University Institute, 2017, https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.ezproxy.uhd.edu/lib/uhdowntown/reader.action?docID=4788068&ppg=197 , 185.

[24] Tommy Curry, “The Fortune of Wells: Ida B. Wells-Barnett’s Use of T. Thomas Fortune’s Philosophy of Social Agitation as a Prolegomenon to Militant Civil Rights Activism,” Transactions of the Charles S. Peirce Society 48, no. 4 (2012): pp. 456-482, https://doi.org/10.2979/trancharpeirsoc.48.4.456, 465.

[25] Tommy Curry, “The Fortune of Wells: Ida B. Wells-Barnett’s Use of T. Thomas Fortune’s Philosophy of Social Agitation as a Prolegomenon to Militant Civil Rights Activism,” Transactions of the Charles S. Peirce Society 48, no. 4 (2012): pp. 456-482, https://doi.org/10.2979/trancharpeirsoc.48.4.456, 458

[26] Roscoe Conkling Simmons, “‘THE SAGA OF T. THOMAS FORTUNE.” ,” The Chicago Defender, May 7, 1949, National Edition edition, p. 18, http://ezproxy.uhd.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/saga-t-thomas-fortune/docview/492779280/se-2?accountid=7109, 18.

[27] Roscoe Conkling Simmons, “‘THE SAGA OF T. THOMAS FORTUNE.” ,” The Chicago Defender, May 7, 1949, National Edition edition, p. 18, http://ezproxy.uhd.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/saga-t-thomas-fortune/docview/492779280/se-2?accountid=7109, 18.

[28] Timothy D. Russell, “Shawn Leigh Alexander, an Army of Lions: The Civil Rights Struggle Before the NAACP. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012. Pp. 382. Cloth $49.95. Paper $27.50.,” The Journal of African American History 98, no. 4 (2013): pp. 642-644, https://doi.org/10.5323/jafriamerhist.98.4.0642, 642.

[29] Tommy Curry, “The Fortune of Wells: Ida B. Wells-Barnett’s Use of T. Thomas Fortune’s Philosophy of Social Agitation as a Prolegomenon to Militant Civil Rights Activism,” Transactions of the Charles S. Peirce Society 48, no. 4 (2012): pp. 456-482, https://doi.org/10.2979/trancharpeirsoc.48.4.456, 459.

[30] Roscoe Conkling Simmons, “‘THE SAGA OF T. THOMAS FORTUNE.” ,” The Chicago Defender, May 7, 1949, National Edition edition, p. 18, http://ezproxy.uhd.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/saga-t-thomas-fortune/docview/492779280/se-2?accountid=7109, 18.

[31] Ida B. Wells-Barnett and Alfreda Duster, Crusade for Justice: The Autobiography of Ida B. Wells (Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press, 2020), https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.ezproxy.uhd.edu/lib/uhdowntown/detail.action?docID=6157250 , 100.

[32] Tommy Curry, “The Fortune of Wells: Ida B. Wells-Barnett’s Use of T. Thomas Fortune’s Philosophy of Social Agitation as a Prolegomenon to Militant Civil Rights Activism,” Transactions of the Charles S. Peirce Society 48, no. 4 (2012): pp. 456-482, https://doi.org/10.2979/trancharpeirsoc.48.4.456, 474.

[33] Ida B. Wells-Barnett and Alfreda Duster, Crusade for Justice: The Autobiography of Ida B. Wells (Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press, 2020), https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.ezproxy.uhd.edu/lib/uhdowntown/detail.action?docID=6157250 , 185.

[34] Jennifer Moses, “Writing ‘The Age: T. Thomas Fortune, the African American Press, and the Unfolding of Jim Crow America, 1880–1930. ”(dissertation, ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 2012), http://ezproxy.uhd.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/writing-age-t-thomas-fortune-african-american/docview/1112071746/se-2?accountid=7109, 4.

[35] Ida B. Wells-Barnett and Alfreda Duster, Crusade for Justice: The Autobiography of Ida B. Wells (Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press, 2020), https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.ezproxy.uhd.edu/lib/uhdowntown/detail.action?docID=6157250 , 204-205.

[36] Shawn Leigh Alexander, An Army of Lions: The Civil Rights Struggle Before the NAACP (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013), https://uh.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/discovery/openurl?institution=01UHO_INST&vid=01UHO_INST:DTOWN&rft.mms_id=991034167469405701&u.ignore_date_coverage=true, xvi.

[37] Ida B. Wells-Barnett and Alfreda Duster, Crusade for Justice: The Autobiography of Ida B. Wells (Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press, 2020), https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.ezproxy.uhd.edu/lib/uhdowntown/detail.action?docID=6157250 , 215-216.

[38] Jennifer Moses, “Writing ‘The Age: T. Thomas Fortune, the African American Press, and the Unfolding of Jim Crow America, 1880–1930. ”(dissertation, ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 2012), http://ezproxy.uhd.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/writing-age-t-thomas-fortune-african-american/docview/1112071746/se-2?accountid=7109, 124-125.

[39] Ida B. Wells-Barnett and Alfreda Duster, Crusade for Justice: The Autobiography of Ida B. Wells (Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press, 2020), https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.ezproxy.uhd.edu/lib/uhdowntown/detail.action?docID=6157250 , 225.

[40] Shawn Leigh Alexander, An Army of Lions: The Civil Rights Struggle Before the NAACP (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013), https://uh.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/discovery/openurl?institution=01UHO_INST&vid=01UHO_INST:DTOWN&rft.mms_id=991034167469405701&u.ignore_date_coverage=true, xv.

[41] Shawn Leigh Alexander, An Army of Lions: The Civil Rights Struggle Before the NAACP (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013), https://uh.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/discovery/openurl?institution=01UHO_INST&vid=01UHO_INST:DTOWN&rft.mms_id=991034167469405701&u.ignore_date_coverage=true, xvii.

[42] Jennifer Moses, “Writing ‘The Age: T. Thomas Fortune, the African American Press, and the Unfolding of Jim Crow America, 1880–1930. ”(dissertation, ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 2012), http://ezproxy.uhd.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/writing-age-t-thomas-fortune-african-american/docview/1112071746/se-2?accountid=7109, 137.

[43] William F. Pinar, “PART THREE: Women and Racial Politics: CHAPTER 7: BLACK PROTEST and the EMERGENCE of IDA B. WELLS,” in The Gender of Racial Politics and Violence in America: Lynching, Prison Rape, & the Crisis of Masculinity (New York, NY: P. Lang, 2001), pp. 417-486, 459.

[44] William F. Pinar, “PART THREE: Women and Racial Politics: CHAPTER 7: BLACK PROTEST and the EMERGENCE of IDA B. WELLS,” in The Gender of Racial Politics and Violence in America: Lynching, Prison Rape, & the Crisis of Masculinity (New York, NY: P. Lang, 2001), pp. 417-486, 482.

[45] Roscoe Conkling Simmons, “‘THE SAGA OF T. THOMAS FORTUNE.” ,” The Chicago Defender, May 7, 1949, National Edition edition, p. 18, http://ezproxy.uhd.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/saga-t-thomas-fortune/docview/492779280/se-2?accountid=7109, 20.